The Curious Case of the Cherny Doktar

This is the story of a Cherny Doktar (dark doctor) who was an Indian. Two Indian boys, whose parents had died of a plague, were picked up by a travelling circus team from somewhere in Punjab. The circus went from India to Hong Kong where something happened and the troupe was disbanded. The two orphans were then adopted by two circus performers, one British and the other Russian. The Russian brought his ward to Vladivostok and then to Omsk in Russia’s Far East.

The Russian adopted his Indian ward as his son and the boy grew up. This was the time when the new Soviet power having overthrown the Czar was threatened with foreign intervention and civil war. The Indian youth joined the Red Army. In the course of the civil war, the Indian turned Soviet soldier saved the life of his commander Surikov but was himself was injured and taken to an army hospital.

In this hospital, Soviet general Kisilev was also undergoing treatment. This dark skinned Soviet soldier drew the general’s attention. He started talking to the boy and was greatly moved by his story. One day he asked the soldier what he would do when the war was over. The boy told him that he wanted to be a doctor as he remembered his parents had died without any medical help.

General Kisilev wrote to Soviet President Kalinin describing everything. He also took interest in the Indian boy and arranged him to be brought to Moscow. He was admitted in the Moscow Second Institute of Medicine where the soldier successfully completed his study and became a doctor. He opted for work in the Central Asian region.

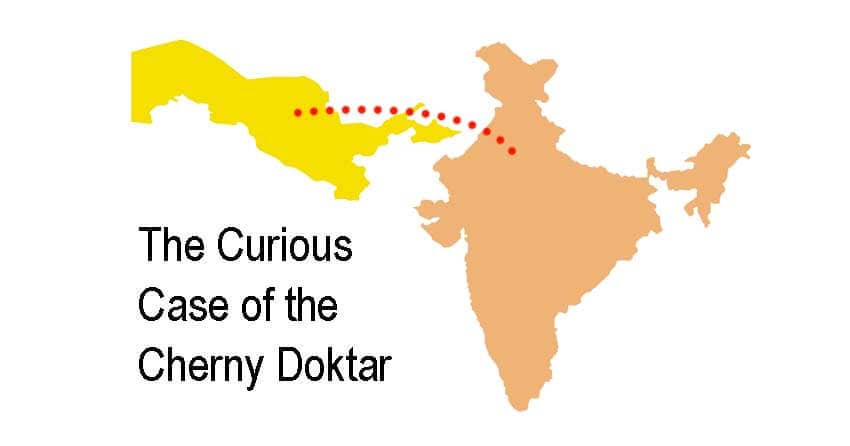

He began working near Samarkand in modern day Uzbekistan, became a very popular doctor and won the nomenclature of Cherny Doktor though his actual name was Dr. Teja Singh. He came probably from a place near Ludhiana and the village he belonged to was possibly called Thiroze. He married and had a daughter and two sons. One son became an engineer in Omsk while the other, also an engineer, was engaged in the task of taming Siberia.

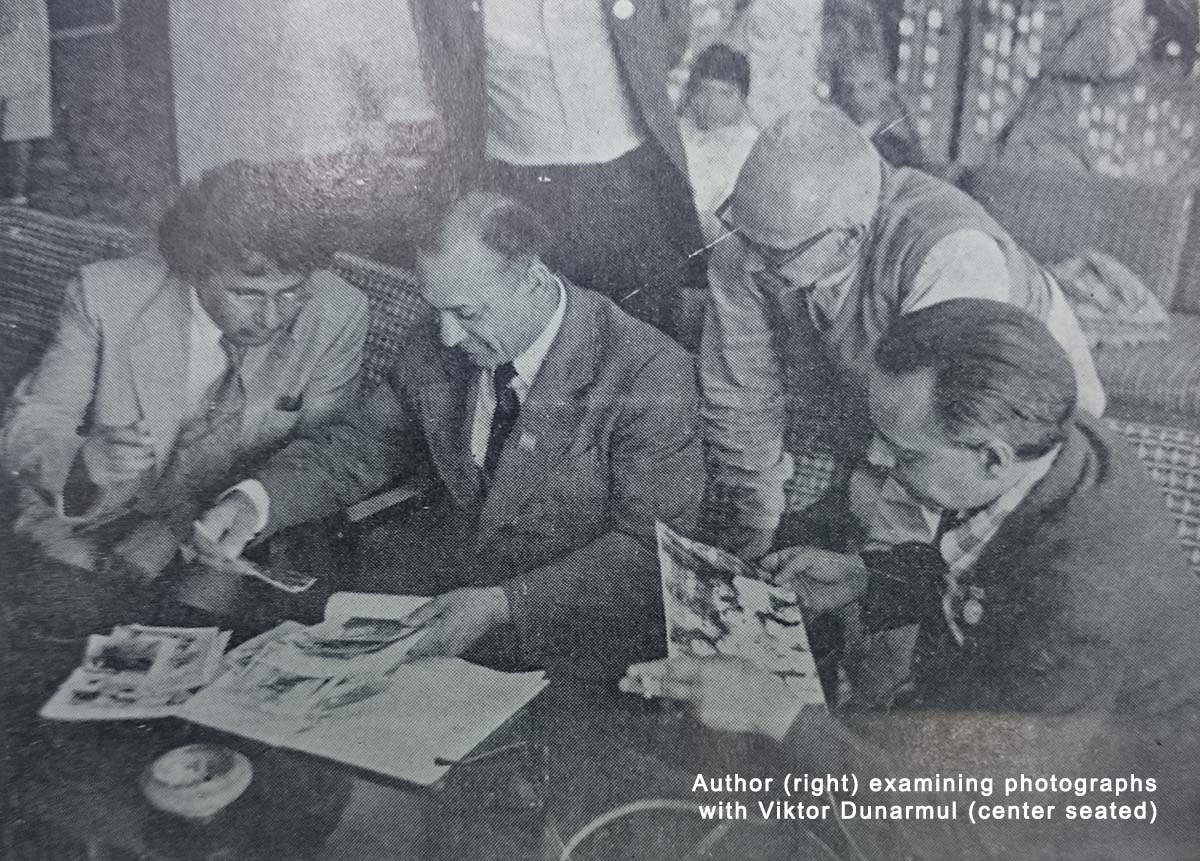

I, unfortunately, could not meet the Cherny Doktor as he had died in 1978, but I did meet another Indian turned Soviet or Uzbek due to history’s peculiar quirk. I met him in Hotel Samarkand while visiting Uzbekistan. He was Alexiev Viktor Dunarmul and he was in search of his heritage. He knew his father was from India and the story Dunarmul narrated to me was to say quite fascinating.

The story goes back to 1904. Dunarmul’s father Budarmul Dunarmul came to the Samarkand-Bukhara region with his uncle and some 300 other Indian traders. Alexiev did not know exactly from where they came. He vaguely remembered his father told him that the place was called something like Sinjkapur but he was not sure.

From whatever Dunarmul remembered, the story unfolded like this. The uncle of Dunarmul’s father wanted to show Budarmul, then about five years old, the world and the way trade is done with foreign countries. The group travelled for about three months by ship (perhaps went to Iran) and then they travelled to Afghanistan. From there they moved to Samarkand where an event took place that changed the course of their lives.

In 1905, a revolution broke out in Russia. The borders were sealed. The Indian traders could not go anywhere and had to stay put. Budarmul, his uncle and some others of the group settled down in the Pakhtachirski district. They did some local trading and took to some other jobs to earn a living. Days rolled into months and months to years, and they waited. Budarmal and another unmarried Indian married local girls.

Then the October revolution of 1917 took place in Russia. The Indians were caught in the whirlpool of events, but all of them harboured the thought of returning to the motherland some day. Only in 1936 they came to know that the Soviet government had passed a decree enabling all foreigners to return home if they wished. For the married two, there was a big problem. By then Budarmul had two children. He loved his family and was torn between two conflicting emotions. He decided to stay back. The others chose to return home.

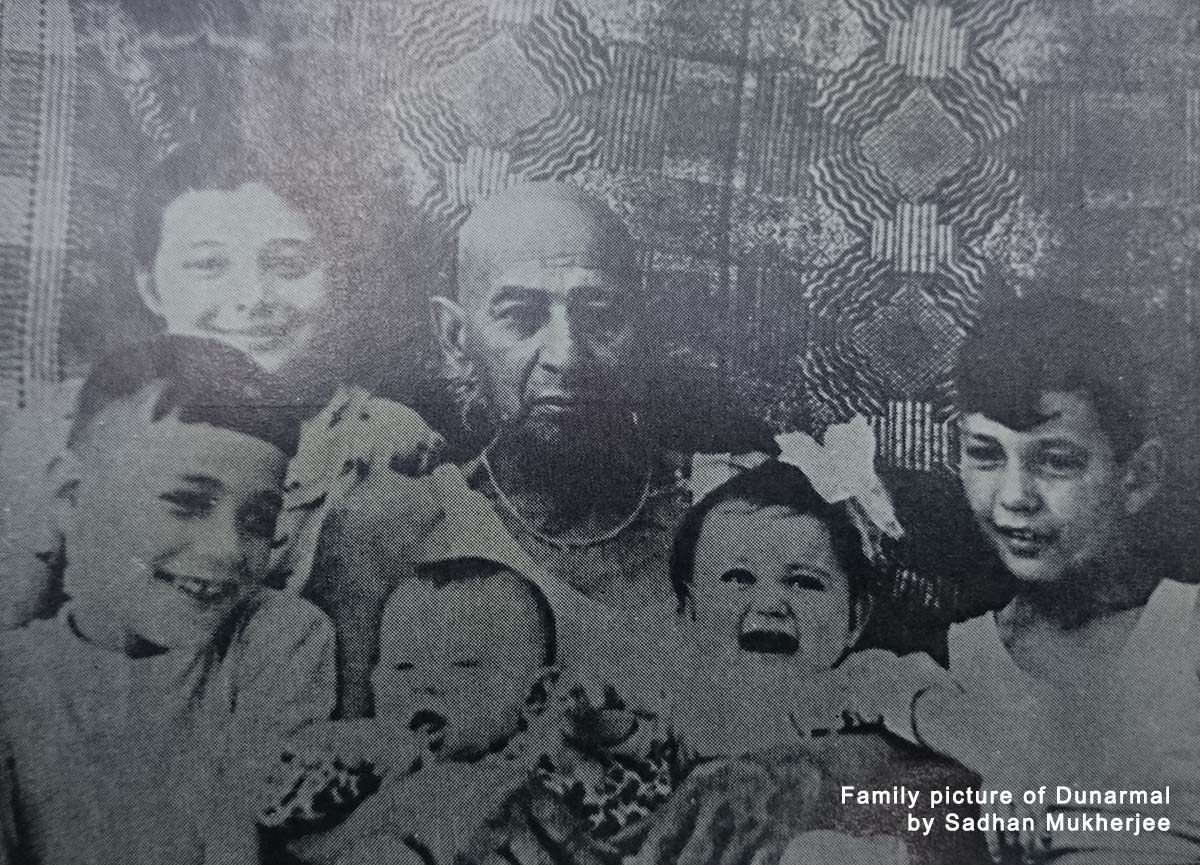

Thus, Budarmul Dunarmul, an Indian, lived on in an alien land which became his second homeland where he completely integrated himself and felt at home. But he never forgot his land of birth, the memory of which time had dimmed but did not completely erase. Budarmul tried to build a miniature India in his house. He kept up Indian traditions and worshipped Hindu Gods the way his uncle had taught him. He used to prepare Indian sweets which he distributed among the local children. He never ate beef. He died at the age of 90 and was cremated with burning logs and butter poured in since no one knew the exact Hindu rites.

Viktor, whom I met, was Dunarmul’s eldest son. His family, even now, does not cook beef. A brass vessel that his father used for worship has been kept in the family museum along with a chess set made of ivory. There are some photographs of his family and some pictures of Dunarmul’s cremation. Viktor’s mother was then still alive.

Viktor could be a Sindhi or a Gujarati from his father’s side. This 50 per cent Indian urged me to write his story so that someone reading it might one day be willing to research and reconstruct his father’s journey. Perhaps those who returned to India from the Pakhtachirski region have left a trace for the researcher to follow.

I visited Samarkand in 1981 and have detailed my experiences in my book Twenty Thousand Kilometers through Soviet Union.