Images of East Bengal

Travelling to East Bengal from the hilly regions of Bihar before independence was quite an experience for me. Those days one did not need any passport and visa. There was certainly no language problem for a Bengali. Just go anywhere on a boat or a steamer in riverine East Bengal.

It was also my earliest travel before I became a hobo in a figurative sense. But that was in yesteryears in British India, not a visit to an independent country, many of which I undertook in later years.

Talking of independent Bangladesh, I particularly recollect a later visit with a World Peace Council delegation to award the Joliot Curie medal to martyred Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who declared Bangladesh’s independence, on 26 March 1971, from Pakistani misrule and was its first prime minister. The medal was handed over to Sheikh Hasina, Bangabandhu’s daughter and the present prime minister of Bangladesh.

A bit of pre-independence history here: By 1900 the British province of Bengal comprised a huge territory of British India stretching from the Ganges region up to Burma. The capital of British India was then in Calcutta. This province was partitioned by Viceroy Lord Curzon in 1905 separating the Hindu majority western part and the Muslim majority eastern part. The western part included present-day Bihar and Orissa and the eastern part included Assam with Dacca as its capital.

The British rulers of India getting wary of the growing nationalist movement, which had its cradle in undivided Bengal, wanted to divide and rule by keeping the two communities alienated from each other.

The 1905 division provoked Bengali intellectuals leading to big protest movements. In 1912, the division was revoked but only after taking out two provinces, Assam and Bihar-Orissa, from contiguous Bengal in order to better control the rising freedom movement.

The capital of British India was also moved from Calcutta to Delhi the previous year. But the freedom movement could not be contained. The trends, the moderate movement and armed struggle, for freedom prevailed.

In 1946, the Cabinet Mission visited India to work out the modalities to hand over power. The Muslim League wanted to demonstrate its strength. Bengal was plunged into a bloodbath. Calcutta suffered what is called a “Week of Long Knives.” The Muslim League called for a ‘direct action day’ for separation of Muslim majority areas. There were largescale riots in Noakhali, a Bengal district and elsewhere and there were communal killings in Bihar. The Muslim League openly asked for a separate state for Muslims.

That aim was materialised in 1947 when the country was divided into India and Pakistan. The eastern part of Bengal went to Pakistan as East Pakistan and the western part remained with India as West Bengal. East Pakistan’s transformation into Bangladesh free from the oppressive regime of Pakistan is yet another story. Even the division was not just a division. Over a million were killed, many while crossing into areas where their own religious brethren lived. The hurried division awarded by Lord Radcliffe left many areas under dispute.

This writer born and brought up in Bihar had no idea about riverine Bengal. Also I did not have any idea of the Hindu-Muslim conflict. My father was a Bengali from East Bengal. He worked as a medical officer in Bihar who was licensed by the British to practice in Bengal, Bihar & Orissa. He had passed from a Medical College in Calcutta.

My plan to visit East Bengal in early 1946, when I was about 12 years old and just before the ‘Week of Long Knives’, was worked out with a couple of relatives. It included a visit to the south-western part of Bengal. The inspiration was my brother-in-law who had some trade dealings in that part of Bengal and was planning to visit the area. He endorsed our idea to accompany him.

The plan called for a visit first to a then little known town of Bagerhat, a trading centre of goods that my brother-in-law dealt with, and from where my ancestors originally came; then to a remote village called Maultala (the place my brother-in-law hailed from), and thereafter to a semi-urban place called Rahmatpur where my forefathers migrated from Bagerhat and settled down.

Our last stop was Barisal, a district town. Barisal district does not have, even today, a single km of railway track, though it had an express train in its name in the good old days from Calcutta.

Only when one visits this part of the Indian subcontinent, does one understand what nadi-matrika Bangla (Bengal, mothered by river) means. East Bengal is really a land crisscrossed, fed and nurtured by rivers and rivulets. Our national song Bande Mataram composed by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee spoke of this land revered as an eternal source of power symbolizing Goddess Durga and motherland, which is endowed with abundant water, highly productive, cooled by the soft breeze and dark green with crops.

The Barisal Express used to start from Sealdah station and took one, straight to Khulna station. It remained operational till 1965 and was shut down when the Indo-Pak War began. We took that train from Sealdah and after arriving at Khulna, tried to look for the Khulna-Bagerhat train. It had already left Khulna making me miss my first trip on a narrow gauge rail line. We went to Rupsa River ghat from the railway station to cross the river in a ferry. By the time we reached, the regular ferry had also left. We hired a small boat to cross Rupsa River and reached Bagerhat town.

Crossing the Rupsa in the dark was quite an awesome experience for this landlubber. This was my first experience in a country boat ride. It was totally dark except for the stars. There was silence, but for the boatman’s oar striking the water and the boat almost gliding over the quiet river. I wondered how the boatman would reach the other side of the river, but he did unerringly, and after some time with a little thud the boat was moored.

Many years later, I had a similar experience when my wife, son and I visited Bangladesh. We went to Comilla from Dhaka crossing the Sitalakshya River by launch. The river, a distributary of Brahmaputra River, is highly turbulent. The soft soil of the banks is often eroded by its rapid flow. The river was quiet in the morning and our launch trip was uneventful.

We crossed the river, went to the Comilla town by taxi and enjoyed the day in that town eating its famous Rasmalai and other eatables. By evening, we returned to the ferry ghat, but there was no launch and no ferry ghat. The wooden jetti was in the river and the rest had been washed away.

My friend who had accompanied us decided to take us across the river by a small boat as the next day we were returning to Kolkata. We got into the boat and soon it became completely dark. We really did not know where we were going, but the boatman knew. These people have an uncanny sense of direction. After some time, we reached the other bank of the river. My son was holding the side edge of the boat at it was about to be moored. Luckily a fellow passenger noticed that and immediately pulled his hand away or else his fingers would have been crushed.

The dimensions of rivers in riverine eastern part of Bengal are huge. There are some 700 major rivers. When in spate one may not be able to see the other side of some of the rivers. There are now proper bridges over Sitalakshya and Rupsa rivers. The Rupsa Bridge is called the Khan Jahan Bridge, named after a famous Sufi Saint who was also the ruler of Bagerhat. He was a Turkish general in the Bengal Sultanate, but I digress.

Reaching Bagerhat, we spent the night at my ancestral house and were treated with a meal of excellent fish curry and rice, and some rice pudding. The tour in the morning of Bagerhat included the tomb of Khan Jahan, Shaat Gambud (Sixty domes) mosque and Ghora Dighi (Horse Lake). Actually there are 81 domes (77 on the roof and 4 on outer pillars – there are in all 60 pillars) in the Shaat Gambud mosque.

Shaat Gambud Mosque

The mosque is now a UNESCO heritage site. These archaeological wonders of Bengal with un-plastered heavy walls represent early Bengal Muslim architecture which also adopted elements of old Bengali style of building. Its most important element was un-plastered thick walls and domes.

Maultala was reached by boat, a trip that took several hours. It is a remote village crisscrossed by many rivulets and canals. The nearest town is Barisal, but there was a high school at Maultala. At that time, the place was almost primeval. People were living by drawing sustenance from available natural resources like fish, fruits and cultivation of rice in small paddy fields.

There were no roads to talk of and no brick houses. There were hardly any toilets in that village except in a few houses. When one wanted to relieve himself or herself, one had to just move out, sit on a dangling branch over the water and do the job. The flowing water took care of everything else. Snakes and crocodiles abounded the area.

A domestic help in my brother-in-law’s family, narrated a story of his own survival from snakebite. One evening he was coming home and in the darkness he put his foot on the back of a cobra. The snake immediately wrapped up his leg and bit him on his right foot. Fortunately this fellow was wearing thick sandals and he used his other foot to crush the head of the cobra and save himself from being totally poisoned. His courage and presence of mind saved his life but he carried a scar on his foot for the rest of his life.

There was another interesting point about the remoteness of that village. This writer was wearing a pair of trousers and some young people of that place had not seen such a garment before. They were curious about it. One of them asked another – how did one get into it? Was it stitched before or after!

Rahmatpur was a better locale and a local trading centre as well. This semi-urban place had produced by then, I was told, nine ICS and a large number of other professionals. Again we stayed at my ancestral house where my relations were still living. It was quite a large household. There was a big courtyard and houses were built on all its four sides. There was a big pond adjacent to the house which provided plenty of fish and nearby fields gave abundant vegetable and rice. There were many beetle nut and palm trees also.

When I was coming to Barisal from Rahmatpur, one of my relations gave me an earthen pot filled with khejur gur (molasses made from date palm juice), derived from the trees within the household. The gur has a follow-up story.

From Rahmatpur, the journey to Barisal was by road. It was a fairly good road and many taxies and buses plied on it. These vehicles are normally overcrowded and one just accommodates oneself wherever one can.

I sat on the mudguard of a taxi holding the earthen pitcher containing the gur. Barisal was only 12 km away but the road was rough. At one place the vehicle jumped so much that the earthen pot hit a small metal projection and the gur started leaking. I had to keep my hand on the hole and at the same time maintain my balance till Barisal was reached. That was the only way to save that gur and I was quite proud of my accomplishment.

Barisal, the district headquarters, is a big city with schools, colleges and other facilities. A distant cousin of mine was attached to the famous BM College as a physical training teacher. He was a very strong man and could harden his muscles to make them feel like stone. He was reputed to have once stopped a bus from moving by holding on to it. The stay at Barisal was short, just overnight, but the gur was disposed off quickly. For me it was a story of both agony and ecstasy!

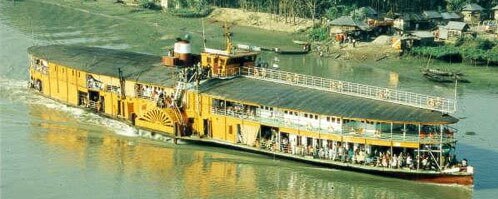

The return journey was by a steamer from Barisal to Khulna. It was an old pedal-type boat with large wheels that cut through the water and pushed the steamer forward. The wheels were turned by a huge steam engine. This writer saw many years later a similar pedal steamer in Helsinki, Finland, that was being used as a tourist attraction.

The journey by steamer from Barisal to Khulna was memorable due to the trip’s beauty. The steamer moved through the winding rivers, frequently whistling and touching some passenger stations. The food prepared by the Mian bhai, as the cook was fondly called, on the steamer was excellent and the fish curry unforgettable.

The travel story in undivided Bengal remains embedded in my memory indelibly with the images of the beauty of riverine East Bengal. The swirling waters and the unending greenery on the banks even today float before my eyes.

It was before the bloodbath that followed between Hindus and Muslims and Bengal was divided into two parts. That part of Bengal also suffered the further post-independence trauma of 1947. Be that as it may, the sights of riverine Bengal which I had never seen before left a lasting imprint on my mind.